O Queen, who art the beauty of Carmel, pray for us

O Queen, who art the beauty of Carmel, pray for usPrimacy of the contemplative spirit.

A direct and intimate experience with God is the basis of Carmel spirituality. Therefore, before any Rule, and in order that the Rule may

be lived when it is formulated, a contemplative spirit and a deep sense of God are required of those who wish to lead the life of Carmel. Of one who understands how to stay before God, no special activity, no special practical disposition is required. While, on the contrary, this sense of God, this thirst to remain in His presence does not belong to that category of realities that a Rule or a technique can call into being. Nor can they be developed in any way ascertainable by the sense. They must exist prior to the realization of a contemplative religious life. God Himself has placed them in the soul's very center and ceaselessly maintains them by means of His grace and His Holy Spirit. This enables us to understand how, although it is not an institution in the western meaning of the term but only a place for the election of a spiritual reality, Carmel has long been able to exist in a free, spontaneous, elementary way and to subsist through the sheer power of its "spirit". This primacy of "spirit", necessary in every religious institute seems even more necessary in Carmel.No exterior activity, whatever be its form, not even fidelity to the Rule, jealously guarded though this must be, can ever take the place of what ought to be the soul of Carmel, we mean the divine current that reaches the depths of man's being and impels the Carmelite to return constantly to his center. This search for God, so essential and so secret, leads of itself to simplicity and spiritual poverty. Instinctively the soul seeking God longs to be disencumbered, to be delivered from all things spiritual and material, in order to think of God alone, to be freed from things of the flesh in order to attain to life in the spirit, and to become altogether spiritual. An idea like this necessarily leads to a spiritual conception of religious life. In fact, nowhere as much as in Carmel must life and observances be vivified by the spirit. That is why a religious as familiar with the origins of Carmel as John of Saint-Samson could write in "De la perfection et decadence de la vie religieuse": "I say that in the days of these first patriarchs and founders, religious life (at Carmel) was a body strongly and excellently animated by spirit, or rather it was all spirit, and all fervent spirit." In fact the ideal of Carmel was always, according to the expression of this same author in "Le vrai esprit du Carmel," "to live in a state of great purity... and to enter into God with all one's strength". It is obvious that John of Saint-Samson here refers to the "Institution des premiers moines," a text highly representative of the spirit of Carmel and of its oldest and purest mystical traditions. In it we read these lines in which the author seeks to describe the life of the first hermits of Carmel. "This life has a double end. The first is ours as the result of our virtuous work and effort, divine grace aiding us. It consists in offering God a holy heart, freed from all stain of actual sin. We attain this end when we are perfect and in Carith (which means ' hidden in charity ')... The second end of this life is communicated to us as God's pure gift. I mean that not only after death but here in this mortal life we can in some way in our hearts taste and experience in spirit the power of the divine presence and the sweetness of heavenly glory. This is called drinking from the torrent of divine pleasure."

At Carmel, purity of heart is never disassociated from delight in things divine. The illusion most to be dreaded has always been to aspire to the highest gifts while disdaining or underestimating the necessary publications. There is another and equally dangerous snare: to try to live a life of high perfection for its own sake and not to aspire to receive the communication of divine life. Carmelite spirituality consists of a supernatural balance which is only possible where there is habitual recourse to the spirit with humility of heart. Although Carmel can see the weakness of its children without astonishment or pessimism, and because it counts on the abundance of divine mercy to remain undisturbed, it has no pity for the slightest shadow that soils the soul. A man who voluntarily harbors some vain attachment in his heart is not a spiritual man. But of what price is purity without spiritual fruitfulness? A detachment in which there is no love? In fact theological primacy makes it impossible for the Carmelite soul to deviate in his pursuit of his double goal. If he aspires to love with the love of God Himself, it is because he is strong in his hope, resolute in his faith, docile in all things to the invitations of the Spirit; it is because he depends on God alone.

Presence to God and zeal for souls.

No one will be surprised that in such a climate a connatural form of activity will spontaneously come into being, we mean prayer understood not so much as an exercise but as being present to God. This is altogether objective and interior, silent and sustained, detached and spiritual.To prayer, as it is understood at Carmel, there are no limits; just as there are no limits to the quality of interior silence that it realizes and the links it fashions between man and his God. According to the measure of the soul's generosity and divine grace, the living God possesses and vivifies this solitude.The exercise of prayer at Carmel is accompanied by a minimum of material conditions. Prayer involves no rigorously prescribed methods. For its development it requires the liberty and fidelity of a soul constantly visited and vivified by the spirit. The Rule faithfully preserves this conception of life with God. The central obligation there laid down is "to meditate night and day on the Law of the Lord". But the example of Elias, as well as an inner exigency, urges the hermits to realize within themselves and without, a spirit of silence and solitude eminently favorable to prayer and of which the desert is the most perfect expression. The desert calls out to the spirit and the spirit calls out to the desert. Between the spirit of Carmel and the desert there is a living relation. Carmel's prayer is the desert in which the spirit dwells. But the desert also induces thirst, and prayer slakes the soul's thirst only to create new capacities for the infinite. "They that drink me shall yet thirst" (Eccl. 24: 29). If it is not without meaning that the word of God was heard in a desert, it is equally significant that the possession of the Promised Land was conditioned by an exodus through that same desert. The soul, too, arrives at a meeting with God, in prayer, only at the price of an exodus painful to sense and spirit. This search for God in silence and solitude, this absence of imposed forms of prayer, a colloquy that is free and truly heart-to-heart in "the place of the espousals"--this is what the desert means, this is what has characterized Carmel from the beginning. Life of God and desert: these timeless realities are never separated in the Old Testament or in the New. The desert of the soul is the very place of God's communication. "The land that was desolate and impassable shall be glad, and the wilderness shall rejoice, and shall flourish like the lily" (Is. 35: 1). The depth in which the intuitions of the Carmelite soul are rooted may make them seem obscure. They are, nevertheless, astonishingly living and active. Consciously or not, the soul unceasingly returns there, to strive to live them fully and directly. If no one is more convinced than the Carmelite of the riches and benefits of tradition, it is also true that no one is more faithfully and lovingly attached to it, yet no one else is more fully persuaded that it is necessary to live personally and to experience in direct contact the mystery of God. Tradition may indeed explain and give a love for the divine realities tasted in prayer: it cannot confer that supreme and incommunicable knowledge which is a fruit of divine wisdom. This comes only to him who suffers God in his soul and in his life.

To remain living and active, the revelation of the divine transcendence and mercy ought to be renewed in each one of us. But as soon as the divine revelation crosses the threshold of our inner dwelling, there is a dawn and centuries vanish. The soul brought back to an absolute beginning watches the flowering of an eternal spring in his own soul. Is not "the verdant one" the meaning of Elias' name? God Himself is there and speaks to the soul. And the soul making her own the words of the prophet, murmurs: "He liveth. He before whom I am".--"As the Lord liveth, and as thy soul liveth. . . " (3 Kgs. 1 7: 1, 4 Kgs. 2: 6). The spirit of Carmel is none other than this power and life which spring from the divine word and seek to enter the soul; none other than this divine presence which is waiting to be received and communicated in a reciprocal gift. Today, no more than in the first days, can this word wait for tomorrows in which it will be accomplished. If the impossible were to take place and the past were suddenly obliterated and tradition no longer existed, and the call of the living God were to sound for the first time in a soul, this call would carry with it the spirit of Carmel in all its freshness, its newness, its eternal richness. Because it is of God and is pure reference to God, this spirit is distinguished by a clarity, a simplicity and a limpidity that are absolute. It has nothing to do with techniques. It fears more than all else material and spiritual encumbrances, multiplicity of means, devotions and spiritual exercises. It is God just as He is that it seeks and desires: God, for the mind all mystery, but for the soul light and delicious knowledge.

The spirit of Carmel is a spirit of childhood, of original life, of newness, of immediate proximity to the divine outpouring. It drinks "of the torrent" without a shell; it does not kneel down but stands erect. It is born of God in all its profundity and passes into man renewing and in truth creating him. That is why this spirit is so immediate, so lacking any kind of transition, so without compromise; so bare, with the bare life of the Old Testament; that is why it is so essential. Strengthened by a power that transcends human means and traverses, without ignoring, what is relative, it discovers its goal and goes straight towards it with a totalitarian exigency of unitive transformation. In short, it advances with a thirst for the absolute, which, once having been felt, can never more be slaked. Without the least shadow of pessimism, the least disdain for the world, the Carmelite is deeply conscious of the infinite distance separating the created from the uncreated, God from His creature. Prayer gives him an understanding, better still, permits him to acquire a kind of experience of the absolute. It is also through prayer that the Carmelite, we read in the second chapter of the "Institution des premiers moines," "tastes in his heart and experiences in his soul the strength of the divine Presence and the sweetness of the glory from above". This does not make the spirit of Carmel aloof toward what is created and toward those who live and grow in the earthy and the relative; this experience of God, on the contrary, is the origin of the most active zeal for souls which is characteristic of the action and person of the prophet Elias. Carmel has never, in fact, separated the apostolic from the contemplative life in its father Elias "who was afire with zeal for the Yahweh of armies" (3 Kgs. 19: 10; 18) with fierce energy preserved in the people of Israel belief in the true God, and who has never ceased to serve as a model to the Order that claims him as founder. In 1275 Nicholas the Frenchman, the seventh prior general, recalled this in these words in his "Ignea Sagitta": "Conscious of their own imperfection, the hermits of Mount Carmel remained long in solitude. But because they desired to be in some way useful to their neighbor, and lest on this point they incur guilt, at times, yet very rarely, they left their hermitage. And as it was with the scythe of contemplation that they harvested in the desert so now in preaching they will scatter the grain on the threshing floor and with open hands they will sow the seed." So it came about that from the beginning Carmelite prayer has had an apostolic side and overflows with missionary fervor. Although these spiritual realities are part of the distant epochs of its pre-history, they have come down through the ages and will always be characteristic of Carmel. This inalienable treasure transmitted to us from century to century by the hermits seems to us in its brilliance and marvelous freshness like an ancient jewel discovered in all its beauty in the desert sands.

THE ROSARY OF SAINT JOSEPH

THE ROSARY OF SAINT JOSEPHThis Rosary, composed of nine mysteries in all, is divided into three parts, each part consisting of three decades, in honor of the thirty years that St. Joseph passed in the company of Jesus and Mary. Like the Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary, each decade is comprised of one Our Father, ten Hail Marys, and a Glory Be. Each part concludes with an act of contrition, asking St. Joseph to obtain pardon and mercy for you. As with the Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary, it may thus be conveniently divided into thirds, not necessarily recited consecutively.

First Part

The Incarnation.

The Perplexity of St. Joseph (as to whether he should abandon his Virgin Spouse).

The Birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ in Bethlehem.

Second Part

The Presentation of the Infant Jesus in the Temple.

The Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt.

The Finding of the Child Jesus in the Temple.

Third Part

The Hidden Life of Jesus at Nazareth.

The death of St. Joseph.

The Coronation of St. Joseph in Heaven.

BLESSING OF THE ROSARY OF ST. JOSEPH

(Formerly reserved to the Order of Carmelites)

P: Our help is in the name of the Lord.

All: Who made heaven and earth.

P: The Lord be with you.

All: May He also be with you.

Let us pray.

Almighty and merciful God, who, out of exceeding love for us,

willed that your only-begotten Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, come

down from heaven to earth for our salvation, taking flesh at the

angel's message in the sacred womb of the blessed Virgin, in

order to snatch us from Satan's tyranny; we humbly beg you in

your boundless goodness to bless + this rosary, made and

dedicated to the honor and praise of the Mother of your Son and

of St. Joseph, her devoted spouse. Let it be endowed with such

power of the Holy + Spirit, that whoever carries it on his

person, or reverently keeps it in his home, may always and

everywhere in this life be shielded from every visible and

invisible foe, and at his death deserve to be presented to you by

these holy spouses, laden with the merits of good works; through

Christ our Lord.

All: Amen.

It is sprinkled with holy water.

Credits: Particia S. Quintiliani, “My Treasury of Chaplets” (WORCESTER: Particia S. Quintiliani, 1994), pp 190-191; Philip T. Weller, “The Roman Ritual, Volume II” (MILWAUKEE: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1964) (www.ctocds.com)

Devotion to the Seven Sorrows and Seven Joys of St Joseph

Devotion to the Holy Face

Devotion to the Holy FaceSister Marie de Saint-Pierre, born in 1816 at Rennes (France), entered the Carmelite monastery at Tours in 1839, having already a rich prayer life and an intense devotion to the Infant Jesus. In 1843 our Lord urged her to undertake herself and to encourage in others reparation for blasphemies, revealing that the adoration of His holy face would honor Him and serve in the work of reparation.

Further, our Lord informed that adoration of His holy face in reparation would render Him the same service as St. Veronica’s wiping from His holy face the spittle, dust, sweat, and blood that covered it as He struggled on the road to Calvary. In a later vision that same year, our Lord told Sr. Marie that His sacred face is “like a divine stamp” that reproduces the image of God in souls. During the course of the revelations, which took place over five years (from 1843 until 1848), our Lord made several promises to the Carmelite nun.

On October 27, 1845, our Lord said, “By My holy face you will work wonders.”

On November 5, 1845, Sr. Marie realized by “divine illumination” that through devotion to His holy face in reparation for the outrages committed against God, our Lord would restore His image in souls by applying to them the virtue of His holy face.

On March 12, 1846, our Lord promised that “all who defend His cause in the work of reparation, whether by their words, their prayers, or their writings, He would Himself present before His eternal Father and that He would give them His kingdom.” Moreover, He promised that at the death of those who strive to atone for blasphemies “He would purify . . . their souls by effac- ing the stains of sin and that He would restore to them their original beauty.”

On November 22, 1846, our Lord assured Sr. Marie that through His holy face she would obtain the conversion of many sinners: “Nothing that you ask in virtue of the holy face will be refused you.”

The Golden Arrow

On March 16, 1844 Our Lord told Sister Mary of St. Peter, “Oh! If you only knew what great merit you acquire by saying even once, ‘Admirable is the Name of God,’ in a spirit of reparation for blasphemy.” He revealed the following prayer to her:

May the most holy,

most sacred,

most adorable,

most incomprehensible

and ineffable Name of God

be forever praised,

blessed,

loved,

adored

and glorified

in Heaven,

on earth,

and under the earth,

by all the creatures of God,

and by the Sacred Heart of Our Lord Jesus Christ,

in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar. Amen.

After receiving this prayer, Sister Mary of St. Peter was given a vision in which she saw the Sacred Heart of Jesus delightfully wounded by this “Golden Arrow” as torrents of graces streamed from It for the conversion of sinners.

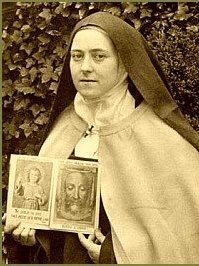

Prayer to the Holy Face (Composed by St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face)

As she herself tells in The Story of a Soul, St. Thérèse had a fervent devotion to the holy face, where she found unfathomable “depths of treasures hidden.” She wrote further, “Ah, I desired that, like the face of Jesus, [and now quoting Isaiah] ‘my face be truly hidden that no one on earth would know me.’”

On August 5, 1899, just a few weeks before her death, to celebrate the Feast of the Transfiguration her sisters brought to the infirmary from the choir the “picture of the holy face she so much loved and hung it where she could see it” Looking at the picture, she said, “Oh, how much good that holy face has done me in my life!”

O adorable face of Jesus,

sole beauty which ravishes my heart,

vouchsafe to impress on my soul

Your divine likeness

so that it may not be possible

for You to look at Your spouse

without beholding Yourself!

O my Beloved,

for love of You I am content

not to see here on earth

the sweetness of Your glance,

nor to feel the ineffable kiss

of Your sacred lips,

but I beg of You

to inflame me with Your love

so that it may consume me quickly

and that soon I (name) may behold

Your glorious countenance in heaven.

Credits:“The Little Book of Carmelite Spirituality and Practice” and various web sites ( www.ctocds.com)

"Practice of the Presence of God" according to Brother Lawrence of the Resurrection (1611-1691), Discalced Carmelite of Paris, translated by Donald Attwater, St Pauls Press

Necessary practices for attaining the Spiritual Life

1. The most holy, the most general and the most necessary practice in the spiritual life is the practice of the presence of God, whereby the soul finds her joy and contentment in His companionship, talking humbly and lovingly to Him always and at all times, but particularly in moments of temptation, of trouble, of spiritual dryness, of revulsion, and especially when we fall into unfaithfulness and sin

2. We should try unceasingly to allow each one of our actions to become a moment of communion with God: not a studied act, but just as it comes from purity and simplicity of heart.

3. We must act recollectedly, not with that impetuosity and thoughtlessness that mark an undisciplined mind; and we must work quietly, calmly and lovingly before God, beseeching Him to accept our labours. By such unceasing turning to God we shall crush the head of Satan and strike his weapons from his hands.

4. During our work and other activities, during our spiritual reading or study, yes, even in our set devotions and vocal prayer, we ought to stop for a moment, as often as we can, in order to worship God in our hearts, to touch Him as it were by stealth as He passes. Since you know that God is with you in all your actions, that He is at the very depth and centre of your soul, why not then pause an instant in your external occupations, and even in your prayers, to worship Him inwardly, to praise Him, to petition Him, to offer Him your heart and to thank Him? What can be more pleasing to God than this quitting many times a day of material things, in order to withdraw within ourselves and worship Him? Furthermore, these moments of recollection little by little purge us of those things of sense, among which alone self-love can flourish. Indeed, we can give God no more convincing evidence of our faithfulness than often to put aside and avoid the creature, that we may rejoice for one moment in the Creator. I am not proposing to you to give up material things entirely; that is impossible: Prudence, the queen of virtues, must be your guide. Nevertheless, I maintain that it is a common mistake among religious people to neglect this periodical recollection in which they may worship God inwardly and enjoy for a few moments the peace of His holy presence. The digression has been long, but no longer that I believe the matter to require; let us then return to our subject.

5. All these acts of worship must be the fruit of faith. We must believe that God is indeed within our hearts, and that we must worship, love and serve Him in spirit and in truth; that He knows all that happens or can happen among His creatures; that He is self-existent, while we depend entirely upon Him; that His infinite perfections are such sovereign excellence and authority that we are required to put everything, ourselves, our souls and bodies at the disposition of His will now and for ever; that in justice we owe Him our thoughts, our words and our deeds. Let us see that we act accordingly.

6. We must diligently examine our conscience to find out of what virtues we are most in need, and which are the most difficult for us to acquire; and to learn our habitual sins and the occasions upon which we generally fall into them. In times of temptation we should go straight to God with complete trust: remain recollected in His presence, humbly worshiping the divine majesty: tell Him our woes and weaknesses: lovingly beg for the aid of His grace; and we shall find in Him the strength that we ourselves lack.

Devotion to the Infant Jesus of Prague

Devotion to the Infant Jesus of PragueIn 1628, the Carmelite friars in Prague received a gift of a beautiful statue of the infant Jesus from a devout noblewoman, a Princess Polixena. They placed the statue in their Church in order to venerate the infant Jesus of Prague, their veneration then being the source of numerous and miraculous favors.

In 1631, when enemies of the Church sacked Prague, they mocked the Holy Infant and threw the statue into a heap of trash in an obscure place. Some years later, Ven. Father Cyril of the Mother of God, a Carmeiite of the Prague monastery, found the statue. One day, while praying before the holy image, Father Cyril heard the consoling words, “Have pity on Me and I will have pity on you; restore My hands and I will give you peace; the more you honor Me, the more I will bless you.”

So many graces, blessings, and miraculous cures came to those who embraced this devotion that it spread throughout the Catholic world and continues to be a source of much grace to this day.

Prayer of Ven. Father Cyril, O.C.D.

Infant Jesus,

unto You With a humble trust I pray.

Through Your mother’s sinless heart,

Help me in my need today.

I believe that You are God,

With a power that is divine.

Full of confidence I ask

That You grant this prayer of mine.

Firm my purpose to amend,

I resolve to grieve no more

That most loving heart of Yours

Out of which all mercies pour.

My whole life I give to You,

I will serve You , Infant King,

Suffer for You patiently,

Do Your will in everything.

Little Jesus, for Your sake

I will love my neighbor, too.

I will seek the other’s good

Through the love I bear for You.

Save me through Your mother’s prayers,

And St. Joseph’s, grant me then

With the heavenly choirs to sing

Endless praise to You. Amen!

Source: “The Little Book of Carmelite Spirituality and Practice”

after www.ctocds.com

Santa Maria della Bruna

Santa Maria della BrunaStory of the Miraculous Painting of Our Lady of Mount Carmel

According to legend, St. Luke painted this image of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, who holds the Infant Jesus in her arms. An expression of great tenderness seems to suggest that our Lady is contemplating the great mysteries of redemption. The Infant’s right hand caresses His mother’s face, and the left grasps the edge of her veil. His position and expression seem to speak of His great love for His mother. A crown on top of her large veil, with star ornaments on the veil at the shoulder, is reminiscent of St. Bernard’s words that Mary is a “brilliant star who enlightens us with the splendor of her virtues.” This image was venerated by the hermit Friars of the Blessed Virgin Mary in their original home on Mount Carmel.

In the beginning of the thirteenth century, the religious of the Carmelite Order, forced by Mohammedans to flee their peaceful solitude by the sea, brought the painting from Mount Carmel to Naples. When settled, their first concern was to place the painting above the high altar in their Church, where it secured countless miracles for the people venerating it. It hung there for more than 100 years, until placed in a side chapel at the order of the Empress Margaret. Then, in the jubilee year of 1500, the ancient picture of Our Lady of Mount Carmel was carried in procession to Rome by the pious Neapolitans. During the pilgrimage, several people were miraculously cured, including Thomas Saccone, who had been blind and lame.

Skeptical of these miracles, “King Frederic II of Naples conceived a plan to test the power of the Heavenly Mother. He ordered that all the sick and infirm [of the city] assemble before the image with written documentation of their maladies. High Mass was celebrated and special hymns were sung, and when the miraculous picture was unveiled, a ray of light fell upon the face of the Madonna, reflecting its brilliance on the assembled sick. The instantaneous healing of each person was authenticated” (Cruz, p. 160).

Sources: “The Little Book of Carmelite Spirituality and Practice”, with additional information from Joan Carroll Cruz's “Miraculous Images of Our Lady” (Rockford: TAN Books and Publishers, Inc., 1993).

after www.ctocds.com

Mater Gratiae (Our Lady of the Bowed Head)

Mater Gratiae (Our Lady of the Bowed Head)This miraculous oil painting was rescued from a heap of rubbish and restored in 1610 by Ven. Dominic of Jesus and Mary, Prepositor General of the Order of Discalced Carmelites. According to the testimony of Ven. Dominic, our Lady spoke to him and promised, "'All those who implore my protection, devoutly honoring this picture, will obtain their petitions, and will receive many graces. Moreover, I shall hearken in a special manner to the prayers that shall be addressed to me for the relief of the souls in purgatory'" (Joan Carroll Cruz, Miraculous Images of Our Lady, [TAN Books & Publishers, Inc., 1993) p. 13].

PRAYER

Lord, Jesus, the hour is come:

glorify Thy Mother that Thy Mother may glorify Thee.

Manifest to all her power and efficacious mediation,

and grant us the favors we implore through her intercession.

Hear us for Thy Mother's sake,

hear us for love of Thy Mother,

we beseech Thee, Lord Jesus!

Show Thyself her Son and procure her triumph

which we desire in view of Thine Own.

That Thy Kingdom may come,

may we have the kingdom of Mary, Mother of Grace. Amen.

PRAYER

Virgin most holy,

Mother of the Word Incarnate,

Treasurer of graces,

and Refuge of poor sinners:

we fly to thy motherly affection

with lively faith,

and we beg of thee the grace

ever to do the will of God.

Into thy most holy hands

we commit the keeping of our hearts,

asking thee for health of soul and body,

in the certain hope that thou,

our most loving Mother,

wilt hear our prayer.

Wherefore with lively faith we say:

followed by Hail Mary three times

Prayers taken from a holy card distributed by the Monastary of Discalced Carmelites, New Orleans, LA, with Nihil obstat and Imprimatur dated March 5, 1949.

after www.ctocds.com

ST. ALBERT'S WATER

ST. ALBERT'S WATERSt. Albert was born at Mount Trapani, in Sicily. His father was of the illustrious family of Abbatibus and was possessed of an immense fortune; his mother, Jeanne de Palizze, was also of the nobility. They had no children, and in their distress vowed to consecrate to Our Lady the child God might give them. Little Albert, the fruit of the promise, was the delight of all for knowledge and virtue far beyond his years. When little more than a child, he received the habit in the Carmelite Monastery near his home, and at his profession all the nobility of the country were present. His life was an extraordinary mingling of prayer, penance, charity to his neighbor, and zeal for souls, to which God added visions and miracles. The Infant Jesus used to appear to him and rest in his arms. He lived to a great age, and in his later years retired into a desert to give himself wholly to prayer. The hour of his death was revealed to him, and many marvels announced its advent, August 7, 1306. At his funeral two Angels appeared to all present and intoned the Mass Os justi of Confessors, instead of the Requiem about to be celebrated. The clergy put on white vestments, as if for a Saint, and all considered that Albert was Canonized from Heaven. At the petition of Blessed John Soreth, his cultus was confirmed by Calixtus III, in 1453.

The use of water, blessed with a relic of the Saint, for the cure of the sick, and particularly for cases of fever, is well established in the Order of the Carmelites: and is justified by countless miracles, which have continued without interruption to the present day. This custom is of heavenly origin. St. Albert, being attacked with a grave illness, had recourse to the Blessed Virgin, who deigned to appear to him, holding a crystal cup, filled with water, which she offered him to drink. The Saint implored her to bless this water, and upon tasting it he was immediately cured.

Inflamed with charity for his neighbor, he besought the Most Holy Virgin to attach a healing power to all water which he would bless in her name and in that of her Divine Son. His prayer was granted; he used this power during life, and has continued to exercise it since his death, with marvellous efficacy, by means of his holy relics, as has been proved by innumerable persons who have taken this water with faith and confidence, while invoking his intercession.

BLESSING OF WATER IN HONOR OF ST. ALBERT, CONFESSOR

(Formerly reserved to the Order of Discalced Carmelites)

The priest is vested in surplice and stole, or at least in a

stole. Assisted by a server who carries a lighted candle, he goes

to the place where the relics of St. Albert are preserved and

reverently exposes them. The water to be blessed is at hand in a

fitting vessel.

P: Our help is in the name of the Lord.

All: Who made heaven and earth.

P: Blessed be the name of the Lord.

All: Both now and forevermore.

P: Lord, hear my prayer.

All: And let my cry be heard by you.

P: The Lord be with you.

All: May He also be with you.

Let us pray.

Lord Jesus Christ, health and strength of all the faithful, who

once completely cured the mother-in-law of your apostle, Peter,

of her high fever; be pleased to bless + and to hallow + this

creature, water. By the prayers of Blessed Albert, your

confessor, whom you called to forsake the world and to enter the

Order of your Mother, the Virgin Mary, and by the humble use of

this water, may all who suffer from fever be delivered from every

infirmity of body and soul, and so deserve to be restored

unharmed to your Church, where they will always offer their

prayers of gratitude. We ask this of you who live and reign

forever and ever.

All: Amen.

Then he reverently takes the relics and immerses them in the

water tracing with them the sign of the cross, and saying:

By the merits of St. Albert, bless, + O Lord, this creature,

water, as you once consecrated the waters of the Jordan through

contact with your sacred body. And grant that all who taste of it

may regain health in body and soul; you who live and reign

forever and ever.

All: Amen.

Antiphon: O Blessed Albert, model of purity, chastity,

continency; intercede with the Mother of mercy that she may keep

us from evildoing in this vale of tears, and help us to attain

everlasting rest after we have laid aside this mortal body.

P: Pray for us, O Blessed Albert.

All: That we may be worthy of Christ's promise.

Let us pray. Almighty and merciful God, grant, we beg you, that

by the prayers of Blessed Albert, your confessor, all the

faithful who reverently drink of this water may regain health in

body and soul, and so persevere in your holy service; through

Christ our Lord.

All: Amen.

Sources: “Carmel, Its History, Spirit, and Saints” (NEW YORK: P.J. KENNEDY & SONS, 1927); Philip T. Weller, “The Roman Ritual, Volume II” (MILWAUKEE: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1964).

after www.ctocds.com

Devotion to Our Holy Father St. Elijah

Devotion to Our Holy Father St. ElijahThose to whom Elijah is little more than a myth, should visit Mount Carmel on July 20 — his Feast. They would behold a revelation. The chronicles of the Order give accounts of it each year, for it is a thing not of the past but of the present. The Holy Mountain is a teeming mass to celebrate Mar Elijah, as it is called. It is not by hundreds, but by thousands, the people are counted. For centuries, they have come on foot, on asses, on camels, on horseback, in carriages, and now, in automobiles! They come in caravans on pilgrimages, and singly on the eve, the pilgrims take their places nearest the Monastery, in every possible costume. The accounts are fascinating, and the ceremonies lend themselves to vivid description, but they would over-pass our space. The tone of the Feast is of innocent joy and profound veneration. There are two statues of Elijah, one in the original grotto under the Sanctuary, reached by steps from the Basilica, another exposed in the Basilica itself; they go from one to the other, praying and asking protection — the devotion to the Prophet enters into the very life of the people.

The good Fathers lend themselves with the utmost charity to all harmless local customs. The archives of the Monastery record many well-authenticated incidents of miraculous favors, and even of apparitions of the Prophet. Children are dedicated to him and offered to God in his grotto. There are always many baptisms. The Arabs of the Greek Catholic Rite wish their children baptised in that spot, and often defer the Sacrament until their yearly pilgrimage.

The closing of the Feast leaves a beautiful picture; the sun sets in the deep blue of the Mediterranien; the Mountain, so lovely in form that the Canticle says of the Bride, “Thy head is as Carmel,” is veiled in shadow, the moon rises over the olives, and it is night! The monks come out upon the terrace, and the traditional illumination takes place, the Monastery is outlined in fire, and as it fades away once more, the pilgrims in their turn continue the display far into the night.

Devotion to the Holy Prophet was brought into the West with the advent of Carmel, and probably no living man has so many adherents, followers, and devotees as he. East and West combine to do him homage: East, because of traditions which hang without dispersion, as clouds in summer, over those dreamy, non forgetting, changeless peoples; West, because of the diffusion of Carmel throughout every nation.

A volume might be filled, indeed many have been filled, with memories of Elijah. The Prophet had no home, but a solitary cave in the mountain, and divine hospitality has opened a home for him in every quarter of the world. And what more in keeping with the idea of divine economy than to believe that when an ambassador of God returns to earth after thousands of years, God should thus provide for him, and how better provide than by constituting him the father of innumerable children who everywhere claim him as their own; who treasure every detail of his life, and, what is most sublime, who offer the supreme Sacrifice many times each day in the humble cave wherein he dwelt, which has be come a Sanctuary enclosed in the Basilica of Carmel. There in the Tabernacle, he will find his Master awaiting him.

The Manual of the Carmelite Order contains prayers for a procession to be made in time of drought or flood, for the holy Prophet both opened and closed the heavens, and in many countries messages are sent to the Monasteries for prayers in either necessity. In May, 1779, there was a great drought in Rome and a Triduum was inaugurated at the four Carmelite Churches in the City. Prayers were said in honor of Elijah, and the Cardinal Vicar of Rome urged the faithful to follow the exercises. The people came in crowds to the statue of the Thaumaturgus, and from the first day the prayer was granted, rain began to fall, and the devotions were continued in thanksgiving. This is only one of many analogous cases.

The Holy Prophet is invoked against pestilence, to avert public calamities, to restore peace of soul, and to draw down the blessings of God on those aspiring to perfection, as is proved in innumerable cases among the Saints and Blessed of Carmel. He is also called upon to avert wars and a remarkable instance is given when Roger of Sicily had to sustain terrible combats against the Saracens. So immediate was the answer of his prayers, that the pious Count built a Church and Monastery in honor of Elijah and presented it to the Carmelites. Many churches, altars, and statues have been erected in his name; states and cities have chosen him for Patron.

This devotion is proper to these latter times when the crimes of men are such as to weary the Divine patience and draw down calamities upon the human race. It is well to seek the charitable aid of him “who has been chosen to appease the wrath of God.” (Ecclesiasticus) Then, too, each day brings us nearer the time when he will come among us with the last message of mercy and forgiveness, ere he sheds his blood for the Lord “in whose sight he stands.”

PRAYER TO ST. ELIJAH

Holy Prophet of God Elijah, Leader and Father of Carmelites, intercede

for us and for the salvation of all.

V: Pray for us, O holy Father Elijah.

R: That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

Let us pray.

Grant, we beseech You, O Almighty God, that we who believe that the

Blessed Elijah Your Prophet and our Father was wonderfully carried up in

a fiery chariot, may by his intercession be raised to the desire of

heavenly things and rejoice in the society of Your saints. We ask this

through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Source: “Carmel, Its History, Spirit, and Saints” (NEW YORK: P.J. KENNEDY & SONS, 1927), pp 240-42.

after www.ctocds.com