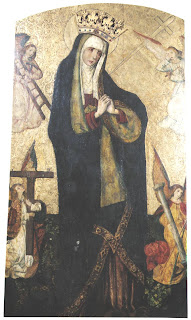

St. Catherine of Sienna, Virgin, Doctor of the Church

St. Catherine of Sienna, Virgin, Doctor of the Church1347-1380

The Middle Ages were drawing to a close and the brave new world of the Renaissance was springing to life when Catherine Benincasa was born. The place was Siena, and the day was the feast of the Annunciation, 1347. Catherine and a twin sister who did not long survive were the youngest of twenty-five children. The father, Giacomo or Jacopo Benincasa, a prosperous wool dyer, lived with his wife Lapa and their family, sometimes comprising married couples and grandchildren, in a spacious house which the Sienese have preserved to the present day. As a child Catherine was so merry that the family gave her the pet name of Euphrosyne, which is Greek for Joy and also the name of an early Christian saint. At the age of six she had the remarkable experience which may be said to have determined her vocation. With her brother she was on the way home from a visit to a married sister, when suddenly she stopped still in the road, gazing up into the sky. She did not hear the repeated calls of the boy, who had walked on ahead. Only after he had gone back and seized her by the hand did she wake as from a dream. She burst into tears. Her vision of Christ seated in glory with the Apostles Peter, Paul, and John had faded. A year later the little girl made a secret vow to give her whole life to God. She loved prayer and solitude, and when she mingled with other children it was to teach them to do what gave her so much happiness.

When Catherine was twelve, her mother, with marriage in mind, began to urge her to pay more attention to her appearance. To please her mother and sister, she dressed in the bright gowns and jewels that were fashionable for young girls. Soon she repented of this vanity, and declared with finality that she would never marry. When her parents persisted in their talk about finding her a husband, she cut off the golden-brown hair that was her chief beauty. As punishment, she was now made to do menial work in the household, and the family, knowing she craved solitude, never allowed her to be alone. Catherine bore all this with sweetness and patience. Long afterwards, in The Dialogue, she wrote that God had shown her how to build in her soul a private cell where no tribulation could enter.

Catherine's father at last came to the realization that further pressure was useless, and his daughter was permitted to do as she pleased. In the small, dimly-lighted room now set apart for her use, a cell nine feet by three, she gave herself up to prayers and fasting; she scourged herself three times daily with an iron chain, and slept on a board. At first she wore a hair shirt, subsequently replacing it by an iron-spiked girdle. Soon she obtained what she ardently desired, permission to assume the black habit of a Dominican tertiary, which was customarily granted only to matrons or widows. She now increased her asceticism, eating and sleeping very little. For three years she spoke only to her confessor and never went out except to the neighboring church of St. Dominic, where the pillar against which she used to lean is still pointed out to visitors.

At times now she was enraptured by celestial visions, but often too she was subjected to severe trials. Loathsome forms and enticing figures would present themselves to her imagination, and the most degrading temptations assailed her. There would be long intervals during which she felt abandoned by God. "O Lord, where wert Thou when my heart was so sorely vexed with foul and hateful temptations?" she asked, when after such a time of agonizing He had once more manifested Himself. She heard a voice saying, "Daughter, I was in thy heart, fortifying thee by grace," and the voice then said that God would now be with her more openly, for the period of probation was nearing an end.

On Shrove Tuesday, 1366, while the citizens of Siena were keeping carnival, and Catherine was praying in her room, a vision of Christ appeared, accompanied by His mother and the heavenly host. Taking the girl's hand, Our Lady held it up to Christ, who placed a ring upon it and espoused her to Himself, bidding her to be of good courage, for now she was armed with a faith that could overcome all temptations. To Catherine the ring was always visible, though invisible to others. The years of solitude and preparation were ended and soon afterwards she began to mix with her fellow men and learn to serve them. Like other Dominican tertiaries, she volunteered to nurse the sick in the city hospitals, choosing those afflicted with loathsome diseases—cases from which others were apt to shrink.

There gathered around this strong personality a band of earnest associates. Prominent among them were her two Dominican confessors, Thomas della Fonte and Bartholomew Dominici, the Augustinian Father Tantucci, Matthew Cenni, rector of the Misericordia Hospital, the artist Vanni, to whom we are indebted for a famous portrait of Catherine, the poet Neri di Landoccio dei Pagliaresi, her own sister-in-law Lisa, a noble young widow, Alessia Saracini, and William Flete, the English hermit. Father Santi, an aged hermit, abandoned his solitude to be near her, because, he said, he found greater peace of mind and progress in virtue by following her than he ever found in his cell. A warm affection bound her to these whom she called her spiritual family, children given her by God that she might help them along the way to perfection. She read their thoughts and frequently knew their temptations when they were away from her. Many of her early letters were written to one or another of them. At this time public opinion about Catherine was divided; many Sienese revered her as a saint, while others called her a fanatic or denounced her as a hypocrite. Perhaps as a result of charges made against her, she was summoned to Florence to appear before the general chapter of the Dominicans. Whatever the charges were, they were completely disproved, and shortly afterwards the new lector for the order in Siena, Raymund de Capua, was appointed her confessor. In this happy association, Father Raymund was in many things of the spirit her disciple. Later he became the saint's biographer.

After Catherine's return to Siena there was a terrible outbreak of the plague, during which she and her circle worked incessantly to relieve the sufferers. "Never did she appear more admirable than at this time," wrote a priest who had known her from girlhood. "She was always with the plague-stricken; she prepared them for death and buried them with her own hands. I myself witnessed the joy with which she nursed them and the wonderful efficacy of her words, which brought about many conversions." Among those who owed their recovery directly to her were Raymund of Capua himself, Matthew Cenni, Father Santi, and Father Bartholomew, all of whom contracted the disease through tending others. Her pity for dying men was not confined to those who were sick. She made it a practice to visit condemned persons in prison, hoping to persuade them to make their peace with God. On one occasion she walked to the scaffold with a young Perugian knight, sentenced to death for using seditious language against the government of Siena. His last words were: "Jesus and Catherine!"

Her deeds of mercy, coupled with a growing reputation as a worker of miracles, now caused the Sienese to turn to Catherine in all kinds of difficulties. Three Dominican priests were especially deputed to hear the confessions of those whom she had prevailed on to amend their lives. In settling disputes and healing old feuds she was so successful that she was constantly called upon to arbitrate at a time when all through Italy every man's hand seemed to be against his neighbor. It was partly, perhaps, with a view to turning the energies of Christendom away from civil wars that Catherine threw herself into Pope Gregory's campaign for another crusade to wrest the Holy Sepulchre from the Turks. This brought her into correspondence with Gregory himself.

In February 1375, she accepted an invitation to visit Pisa, where she was welcomed with enthusiasm. She had been there only a few days when she had another of the spiritual experiences which seem to have presaged each new step in her career. She had made her Communion in the little church of St. Christina, and had been gazing at the crucifix, when suddenly there descended from it five blood-red rays which pierced her hands, feet and heart, causing such acute pain that she swooned. The wounds remained as stigmata, visible to herself alone during her life, but clearly to be seen after her death.

She was still in Pisa when she received word that the people of Florence and Perugia had entered into a league against the Holy See and the French legates. The disturbance had begun in Florence, where the Guelphs and the Ghibellines united to raise a large army under the banner of freedom from the Pope's control, and Bologna, Viterbo, and Ancona, together with other strongholds in the papal domain, rallied to the insurgents. Through Catherine's untiring efforts, the cities of Lucca, Pisa, and Siena held back. From Avignon, meanwhile, after an unsuccessful appeal to the Florentines, the Pope, Gregory XI, sent Cardinal Robert of Geneva with an army to put down the uprising, and laid Florence under an interdict. The effects of the ban on the life and prosperity of the city were so serious that its rulers sent to Siena, to ask Catherine to mediate with the Pope. Always ready to act as a peacemaker, she promptly set out for Florence. The city's magistrates met her as she drew near the gates, and placed the negotiations entirely in her hands, saying that their ambassadors would follow her to Avignon and confirm whatever she did there. Catherine arrived in Avignon on June 18, 1376, and was graciously received by the Pope. "I desire nothing but peace," he said; "I place the affair entirely in your hands, only I recommend to you the honor of the Church." As it happened, the Florentines proved untrustworthy and continued their intrigues to draw the rest of Italy away from allegiance to the Holy See. When their ambassadors arrived, they disclaimed all connection with Catherine, making it clear by their demands that they did not desire a reconciliation.

Although she had failed in this matter, her efforts in another direction were successful. Many of the troubles which then afflicted Europe were, to some degree at least, due to the seventy-four-year residence of the popes at Avignon, where the Curia was now largely French. Gregory had been ready to go back to Rome with his court, but the opposition of the French cardinals had deterred him. Since in her letters Catherine had urged his return so strongly, it was natural that they should discuss the subject now that they were fact to face. "Fulfill what you have promised," she said, reminding him of a vow he had once taken and had never disclosed to any human being. Greatly impressed by what he regarded as a supernatural sign, Gregory resolved to act upon it at once.

On September 13, 1376, he set out from Avignon to travel by water to Rome, while Catherine and her friends left the city on the same day to return overland to Siena. On reaching Genoa she was detained by the illness of two of her secretaries, Neri di Landoccio and Stephen Maconi. The latter was a young Sienese nobleman, recently converted, who had become an ardent follower. When Catherine got back to Siena, she kept on writing the Pope, entreating him to labor for peace. At his request she went again to Florence, still rent by factions, and stayed there for some time, frequently in danger of her life. She did finally establish peace between the city governors and the papacy, but this was in the reign of Gregory's successor.

After Catherine returned to Siena, Raymund of Capua tells us, "she occupied herself actively in the composition of a book which she dictated under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit." This was the mystical work, in four treatise, called The Dialogue of St. Catherine.

Her health was now so impaired by austerities that she was never free from pain; yet her thin face was usually smiling. She was grieved by any sort of scandal in the Church, especially that of the Great Schism [The Schism lasted from 1378 to 1418, when Church unity was restored with the election of Pope Martin V.] which followed the death of Gregory XI. Urban VI was elected as his successor by the cardinals of Rome and Clement VII by the rebellious cardinals of Avignon. Western Christendom was divided; clement was recognized by France, Spain, Scotland, and Naples; Urban by most of North Italy, England, Flanders, and Hungary. Catherine wore herself out trying to heal this terrible breach in Christian unity and to obtain for Urban the obedience due to the legitimate head. Letter after letter was dispatched to the princes and leaders of Europe. To Urban himself she wrote to warn him to control his harsh and arrogant temper. This was the second pope she had counseled, chided, even commanded. Far from resenting reproof, Urban summoned her to Rome that he might profit by her advice. Reluctantly she left Siena to live in the Holy City. She had achieved a remarkable position for a woman of her time. On various occasions at Siena, Avignon, and Genoa, learned theologians had questioned her and had been humbled by the wisdom of her replies.

Although Catherine was only thirty-three, her life was now nearing its close. On April 21, 1380, a paralytic stroke made her helpless from the wait downwards, and eight days later she passed away in the arms of her cherished friend, Alessia Saracini. The Dominicans at Rome still treasure the body of Catherine in the Minerva Church, but Siena has her head enshrined in St. Dominic's Church. Pope Pius II canonized Catherine in 1461. The saint's talents as a writer caused her to be compared with her countrymen, Dante and Petrarch. Among her literary remains are the Dialogue and some four hundred letters, many of them of great literary beauty, and showing warmth, insight, and aspiration. One of the important women of Europe, Catherine's gifts of heart and mind were used in the furtherance of the Christian ideal.

Letter to Gregory XI

In the name of Jesus Christ crucified and of sweet Mary:

Most holy and most reverend my father in Christ Jesus: I Catherine your poor unworthy daughter, servant and slave of the servants of Christ, write to you in His precious blood; with desire to see you a good shepherd. For I reflect, sweet my father, that the wolf is carrying away your sheep, and there is no one found to succor them. So I hasten to you, our father and our shepherd, begging you on behalf of Christ crucified to learn from Him, who with such fire of love gave Himself to the shameful death of the most holy cross, how to rescue that lost sheep, the human race, from the hands of the demons; because through man's rebellion against God they were holding him for their own possession.

Then comes the Infinite Goodness of God, and sees the evil state and the loss and the ruin of these sheep, and sees that they cannot be won back to Him by wrath or war. So, notwithstanding they have wronged Him—for man deserves an infinite penalty for his disobedient rebellion against God—the Highest and Eternal Wisdom will not do this, but finds an attractive way, the gentlest and most loving possible to find. For it sees that the heart of man is in no way so drawn as by love, because he was created by love. This seems to be the reason why he loves so much: he was created by nothing but love, both his soul and his body. For by love God created him in His Image and Likeness, and by love his father and mother gave him substance, conceiving and bearing a son.

God, therefore, seeing that man is so ready to love, throws the book of love straight at him, giving him the Word, His Only-Begotten Son, who takes our humanity to make a great peace. But justice wills that vengeance should be wrought for the wrong that has been done to God: so comes Divine Mercy and unspeakable Charity, and to satisfy justice and mercy condemns His Son to death, having clothed him in our humanity, that is, in the clay of Adam who sinned. So by His death the wrath of the Father is pacified, having wrought justice on the person of His son: so He has satisfied justice and has satisfied mercy, releasing the human race from the hands of demons. This sweet Word jousted with His arms upon the wood of the most holy Cross, death fighting a tournament with life and life with death: so that by His death He destroyed our death, and to give us life He sacrificed the life of His body. So then with love He has drawn us to Him, and has overcome our malice with His benignity, in so much that every heart should be drawn to Him; since greater love one cannot show—and this He himself said—than to give one's life for one's friend. And if He commended the love which gives one's life for one's friend, what then shall we say of that most burning and perfect love which gave its life for its foe? For we through sin had become foes of God. Oh, sweet and loving Word, who with love hast found Thy flock once more, and with love hast given Thy life for them, and hast brought them back to Thy fold, restoring to them the Grace which they had lost!

Holiest sweet father of mine, I see no other way for us and no other aid to winning back your sheep, which have left the fold of Holy Church in rebellion, not obedient nor submissive to you, their father. I pray you therefore, in the name of Christ crucified, and I will that you do me this grace, to overcome their malice with your benignity. Yours we are, father! I know and realize that they all feel that they have done wrong; but although they have no excuse for their crimes, nevertheless it seemed to them that they could not do differently, because of the many sufferings and injustices and iniquitous things they have endured from bad shepherds and governors. For they have breathed the stench of the lives of many rulers whom you know yourself to be incarnate demons, and fallen into terrible fears, so that they did like Pilate, who not to lose his authority killed Christ; so did thy, for not to lose their state, they maltreated you. I ask you then, father, to show them mercy. Do not regard the ignorance and pride of your sons, but with the food of love and your benignity inflict such mild discipline and benign reproof as shall satisfy your Holiness and restore peace to us miserable children who have done wrong.

I tell you, sweet Christ on earth, on behalf of Christ in Heaven, that if you do this, without strife or tempest, they will all come grieving for the wrong they have done, and lay their heads on your bosom. Then you will rejoice, and we shall rejoice, because by love you have restored the sheep to the fold of Holy Church. And then, sweet my father, you will fulfill your holy desire and the will of God by starting the holy Crusade, which I summon you in his name to do swiftly and without negligence. They will turn to it with great eagerness; they are ready to give their lives for Christ. Ah me, God, sweet Love! Raise swiftly, father, the banner of the most holy Cross and you will see the wolves become lambs. Peace, peace, peace, that war may not delay that happy time!

But if you will wreak vengeance and justice, inflice them on me, poor wretch, and assign me any pain and torment that may please you, even death. I believe that through the foulness of my iniquities many evils have occurred, and many misfortunes and discords. On me then, your poor daughter, take any vengeance that you will. Ah me, father, I die of grief and cannot die! Come, come, and resist no more the will of God that calls you; the hungry sheep await your coming to hold and possess the place of your predecessor and Champion, Apostle Peter. For you, as the Vicar of Christ, should abide in your own place. Come, then, come, and delay no more; and comfort you, and fear not anything that might happen, since God will be with you. I ask humbly your benediction for me and all my sons; and I beg you to pardon my presumption. I say no more. Remain in the holy and sweet grace of God—Sweet Jesus, Jesus Love.

(Letters of Saint Catherine of Siena, translated by Vida D. Scudder. 1906)

Published by John J. Crawley & Co., Inc. New York,

Nihil Obstat: John M. A. Fearns, S.T.D., Censor Librorum

Imprimatur: +Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York

August 7, 1954

The image is "St. Catherine of Siena Besieged by Demons", tempera on wood, about 1500, National Museum in Warsaw

Read whole post......