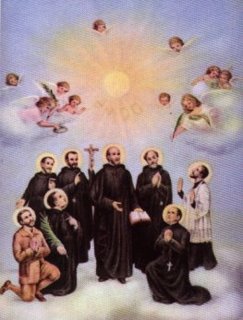

JESUIT MARTYRS OF NORTH AMERICA (†1642-1649)

JESUIT MARTYRS OF NORTH AMERICA (†1642-1649)Spiritual Bouquet: Each will receive his own reward according to his labor. I Cor. 3:8

The Holy North American Martyrs are eight in number; five died in what is now Canada, three in what is now the United States. All are Jesuits, all are French in origin. They came in the 1640's to New France, to add their strength to that of the Franciscan Recollets, who had preceded them by a few years. There was not yet any bishop to assist them; the first bishop of Quebec, Blessed Monsignor Francis Montmorency de Laval, arrived only in 1658. Words strive in vain to convey to a comfortable world the virtue of the first missionaries, and to describe the difficulties confronted by these heros desiring to implant Christianity amid the savage nations of the north. Building materials, chapel accessories, everything in effect had to be imported from France; the Indian languages were varied and difficult; customs were at best non-Christian; insects infested the woods where they dwelt; the tribes were migrant and had to be followed from place to place. There were less belligerent ones who responded rapidly to the pacifying and sanctifying influences of the Faith, but the Iroquois of the northeast were dreaded, and it was to them that the eight martyrs all fell victims, over a period of seven years.

The Martyrs of Canada:

Father Antoine Daniel was the first to die in Canada, after ten years among the Hurons. The chapel of the village where his mission stood was filled with his faithful Christians, and he had just finished saying Mass, when the Iroquois attacked in July of 1648. The men ran to the palisades; the priest, when the invaders broke through, went to the chapel door and faced the Iroquois, warning them of God’s anger. They slew him at once and threw him into the chapel they had already set on fire, still occupied by the women and children.

Saint John de Brebeuf, “the giant of the Huron missions” was a native of Normandy, noted for his physical height and strength and still stronger love of God. Arriving in 1625, at the age of 32 years, he spent three years with the Hurons of Ontario, winning their love and respect to such a degree that they wept when he was recalled to Quebec City for a time in 1628. “We still do not know how to adore the Master of life as you do!” Political questions obliged him to return to Europe in that year, but he was back in Canada in 1633, and among his Hurons the following year. He labored until 1649, in which year the luminous Cross he had seen in the sky the year before, presage of his martyrdom, became a reality for this glorious father of the Faith in America. The Iroquois took him prisoner in the village of Saint Louis near the Georgian bay of Lake Huron. He was tortured, scalped; pieces of his flesh were removed and eaten before his eyes; boiling water was poured over him, hatchets heated red-hot were placed on his chest, back and shoulders. He did not utter a single cry. His death occurred in March of 1649.

His young companion in the mission, Father Gabriel Lallemant, 39 years old in that year and of a delicate constitution, was martyred the next day; he had been forced to witness the death of his beloved Father Brebeuf. He cried out: “Father, we are given up as a spectacle to the world, the Angels and men!” And he went up to him and kissed his bleeding wounds. Facing the same fate afterwards, he knelt down and embraced the stake to which he was to be tied, to make his final offering to God. He himself survived for longer still, seventeen hours. The Iroquois set fire to the bark they had attached to him; he was “baptized” in mockery of the faith, in boiling water, not once but many times. The savages cut the flesh of his thighs to the bone and held red-hot axes in the wounds. They finally tired of their task and finished him with a blow from an axe.

Nine months after the martyrdom of these two, Saint Charles Garnier, also missioned with the Hurons, fell victim in his turn. He was a valiant priest who had said: “The source of all gentleness, the sustenance of our hearts, is Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament.” He was of a wealthy family, and as a student in the Jesuit college of Clermont, would deposit his weekly allowance in the church’s collection box for the poor. In the mission he slept without a mattress, and when traveling with the Indians, would carry the sick on his shoulders for an hour or two to relieve them. He died the day before the feast of the Immaculate Conception, on December 7, 1649, while aiding the wounded and the dying; an Iroquois fired two bullets directly into his chest and abdomen. Seeing a dying man near him, twice he tried to stand and go to him, and twice he fell heavily. Another Iroquois then ended his life with an axe.

Saint Noel Chabanel had been a professor in France; he suffered the temptation to return to Europe when he saw clearly the state of the souls of the natives. He overcame it and made a vow in writing of perpetual stability in the Huron mission. He died alone when, pursued by the Iroquois in the company of a few of his Huron neophytes, he had to stop, exhausted, in the woods. He told the others to flee. It was later that an apostate Huron avowed he had killed him in hatred of the Christian religion and cast his body into a river. He died on the feast of Our Lady which he particularly loved, that of the Immaculate Conception, one day after the martyrdom of Father Garnier, on December 8, 1649.

The Martyrs of New York State:

The great missionary Isaac Jogues was martyred, as it were, twice; after being surprised by the Iroquois while traveling, he might have escaped from the midst of his Hurons who were being seized at the same time, but did not want to abandon them. He was tortured in ways like those we have described for the others, but he survived and was held prisoner under the most painful conditions for long months, by the Iroquois of what is now New York State. He finally escaped and returned to Europe, aided by the Dutch. He was not recognized when he knocked on the door of the Jesuit house in Paris. When the Holy Father Urban VIII was asked for a dispensation for him to say Mass, since his fingers had been badly mutilated, he replied: “Can one deny the right to say Mass to a martyr of Christ?” The Saint returned to Quebec and offered himself for an Iroquois mission, saying he would not return. He was killed in 1646 by a sudden blow of an axe from behind, by a savage of the mission where he stayed.

During the original captivity of Father Jogues, his assistant, Brother René Goupil, was with him, a prisoner like himself. He was the first of the Jesuit martyrs to die. He was a donné, a coadjutor Brother who desired to come to the American missions to assist the priests, having been found to have too unstable a health to be ordained. He was said never to have lost the smile which characterized his gentle disposition. He died in 1642, when least expecting it, from the blow of an axe, while he was helping a little child to make the sign of the cross. Father Jogues succeeded in burying his young assistant, at once calling him a martyr, because slain in hatred of God and the Church, and of their sign which is the Cross, and while exercising ardent charity towards his neighbor.

And finally, Saint Jean de la Lande, who had “the heart of an apostle,” engaged himself to work as an auxiliary of the missionaries, for love of Jesus Christ and souls. On the day of his departure, he was expecting to meet with death in the new world. Unafraid of the sufferings he knew awaited him, he accompanied Father Jogues and was slain in the same mission as the priest, on the following day, October 19, 1646.

It seems fitting to include here the picture of Blessed Kateri who was remarkable for her holiness and is the first beatified tribal native Indian of North America. May the Name of the Lord be blessed for ever.

Source: Nos Gloires (L’Église du Canada), by Gerard Champagne (Jésus Marie et Notre Temps: Montreal, 1976).

after www.magnificat.ca